People with obesity are suffering more and dying at higher rates from COVID-19, according to a report released by the World Obesity Federation in March. This makes obesity a high-risk factor, similar to other comorbidities such as diabetes and heart disease.

“We know that clearly when you have obesity, when you’re carrying a lot of excess weight, first of all you probably have comorbidities…which all work together to make you less healthy and less able to fight a virus. But also, that you have an inflammatory response — essentially that [you are more] likely to have a very bad outcome,” said Johanna Ralston, CEO of the World Obesity Federation, during a recent ICFJ Global Health Crisis Reporting Forum webinar.

At the time of the report’s release, 2.2 million of the 2.5 million deaths reported due to COVID-19 were in countries where over half the population is overweight, said Ralston. Only some small island states with more effective public health measures have been able to better control the virus despite higher obesity rates, she added.

Why obesity rates are increasing

Obesity rates have been increasing across the globe for decades in both children and adults due in large part to genetics, increased intake of drugs, and higher consumption of soft drinks and ultra-processed foods.

COVID-19 has exacerbated the risks and prevalence of obesity, said Ralston, as the pandemic has strained food systems and supply chains, altered eating patterns especially among children, and increased food insecurity. People have also been less physically active, and experienced more harm to their mental health, among other factors.

[View past webinars and key quotes]

Solutions during COVID-19 and beyond

As we continue to fight the pandemic across the globe, solutions to address obesity must be implemented in order to save lives. “We’re not going to tackle obesity using one thing...we have to do many things at the same time,” said Ralston.

Solutions such as changing labeling, eliminating trans fat from diets, instituting sugar taxes and altering marketing can all work to combat obesity. They have to go beyond the pandemic-driven increase in obesity, said Ralston.

There are approximately 800 million people living with obesity today. While the World Health Organization and the United Nations have introduced targets in the past to reduce obesity, they are not being met. “The roots...that are driving [obesity], we’re going to communicate into a clear map forward,” said Ralston.

Bringing the obesity agenda to the forefront

Obesity is a non-communicable disease — in other words, one that can’t be transmitted from one person to another. Non-communicable diseases are now the leading cause of death globally, but since they manifest over extended periods of time, they don’t receive as much attention among policy-makers.

In some cultures, extra weight is also seen in a positive light and can even be perceived as prosperous. The goal is to combat “unhealthy weight” that has direct correlation to complications such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension and the like, said Ralston.

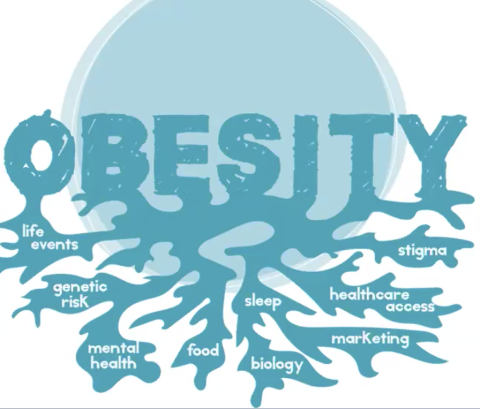

Moving away from stigmatizing language and imagery is also important. “People saw obesity as a sign of weakness and laziness; now we know there’s a much more complex genetic storm behind it and what food people have available, too…there are many drivers, yet we portray people with obesity as bringing this on themselves.”

While reliable data on obesity rates is not always available either, being rigorous with estimates is also important. Body Mass Index (BMI) may be an imperfect measure, but it is the lowest common denominator and a good place to start, said Ralston.

We still don’t know enough about obesity and its connection to COVID-19. We do know that obesity has actual economic and social costs.

Ralston hopes the disease will be at the top of the global agenda and obesogenic environments will be combated with social and policy changes. “We couldn’t have stopped the pandemic by addressing obesity, but we could’ve stopped a lot of people dying,” she said.

Graphic from presentation by Johanna Ralston.

Inaara Gangji is a freelance Tanzanian-Indian journalist who focuses on gender, social justice and development. Usually based out of Doha but with work spanning the U.S., Middle East and Africa.