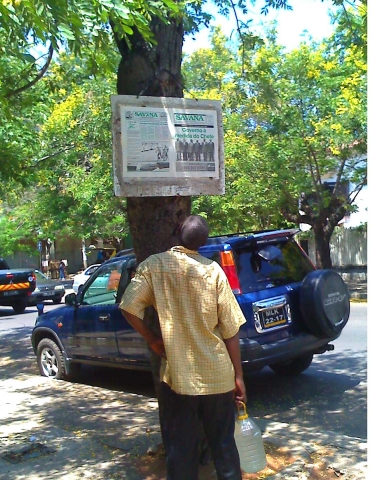

On Thursday afternoon, when Savana hits the streets, a copy is posted outside the newsroom for passersby to read for free. Who knows if it will inspire some to become journalists?

I am the first person in my family and among my friends to go to university. My parents are not schooled. They are peasants. They can’t speak Portuguese, they speak makuhwa. My father, though, was a cheke, a mwalima, learned in the Koran and respected in the village. We lived in Metarica, in Niassa province, in Mozambique s farthest north.

On Thursday afternoon, when Savana hits the streets, a copy is posted outside the newsroom for passersby to read for free. Who knows if it will inspire some to become journalists?

We are 11 siblings and I am the seventh, born in 1983. The eldest went to high school and became a border policeman. My other brothers work on the land. My sisters got married early. Two siblings died of disease. I was good at school so my eldest brother helped me financially to go to high school in Lichinga, the provincial capital.

On Thursday afternoon, when Savana hits the streets, a copy is posted outside the newsroom for passersby to read for free. Who knows if it will inspire some to become journalists?

I didn’t know how one gets into university. I didn’t dare think about it. But two of my classmates were admitted, and my grades were better than theirs. Maybe I had a chance. They explained to me how to apply.

My brother, though, wanted me to start working. He thought I had studied enough and should now help the family.

But the only job available for a high school graduate in the rural areas is to teach at rural schools. Most of my classmates went for this but I wanted something else. It is a dead-end job. You teach kids, then you marry and have kids, and you are stuck in the village forever. I wanted to go to university and study journalism.

As a child, I never saw a TV newscast or read a newspaper. Metarica is really remote. At age 17, at the public library in Lichinga I discovered the daily Noticias and the weekly Savana. I liked that these journalists had opinions and were shaping public opinion. I wanted to be one of them.

I sought the advice of my parents in Metarica. They told me to do what I really wanted to do. But they had no money to give me so I took a job. During three weeks I planted maize for a rich farmer - I am very good at hoeing - and earned about US$30. I saved half for the university exam. With the other half I bought shoes, trousers and a white shirt at the second-hand clothes market, and I went to Lichinga to take the admission exam.

I lived with a friend and studied hard at the library every day. The exam is tough. About 28,000 apply but only 4,000 are admitted. It takes a month for the results to reach Niassa by mail. They are posted earlier on the internet but I didn’t have money to go to a cyber café.

Eventually I overcame my shyness and asked a professor to check the admissions list in his computer. He said my name was not there. I was so depressed. My friends tried to console me, saying it is not the end of your life, but to me, it was. I shut myself in my room for a whole day.

The following morning, a friend rushed into the yard shouting that the list was affixed in the square and that my name was there. I could not believe it. I ran, and there it was. I had been accepted!

Now I had a problem. There was no mention of room and tuition. How would I get to Maputo and survive? It turned out that the scholarships were affixed elsewhere. Another friend ran to tell me I had got one. My dream was coming true.

Now I needed US$80 to get to Maputo, 1800 kms away, a 3-day and 3-night journey by minibus, via Malawi, back into Mozambique through Tete, because the roads were so bad. My eldest brother didn’t want to help; we had a bit of a quarrel about my decision. Instead, I went to my sister in law, and she convinced him to give me the money I needed and a bit more.

On the trip, a passenger told me that I had made a poor career choice, that I should study sociology. I was worried. But by the second year I knew he was wrong and I was right. I have not regretted my choice.

My father died in 2004, the year I came to Maputo. A neighbour who wanted to chase him from the mosque bewitched him. He went mad and died. I regret that once I told him that only my brother and I had studied in the family. He said: ”How can you say that? I studied Arabic and the Koran. I am learned, in my way”. Now I understand that he answered with logic and dignity. He had knowledge. I wish I could tell him that he was right.

I did not see my mother until I finished university. I never had money for the trip. There is no cellphone reception in Metarica but my sisters live a nearby town that has and once a week they give me all the news about the family.

Last year I was hired to do fieldwork in a research project on women and local governance in Niassa province and managed to see my mother twice. She was so happy.

I have not sent her yet the copies of Savana with my story on measles and polio. My dream has come true.

I want my younger brothers to study and will help them as much as I can. For us, the poor, investing in education is the only way out of poverty.