This article was first published Jan. 14 by the Columbia Journalism Review.

News has migrated from print to the web to social platforms to mobile. Now, at the dawn of a new decade, it is heading to a place that presents a whole new set of challenges: the private, hidden spaces of instant messaging apps.

WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, Telegram, and their ilk are platforms that journalists cannot ignore — even in the U.S., where chat-app usage is low. “I believe a privacy-focused communications platform will become even more important than today’s open platforms,” Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s CEO, wrote in March 2019. By 2022, three billion people will be using them on a regular basis, according to Statista.

But fewer journalists worldwide are using these platforms to disseminate news than they were two years ago, as ICFJ discovered in its 2019 “State of Technology in Global Newsrooms” survey. That’s a particularly dangerous trend during an election year, because messaging apps are potential minefields of misinformation.

American journalists should take stock of recent elections in India and Brazil, ahead of which misinformation flooded WhatsApp. ICFJ’s “TruthBuzz” projects found coordinated and widespread disinformation efforts using text, videos, and photos on that platform.

It is particularly troubling given that more people now use it as a primary source for information. In Brazil, one in four internet users consult WhatsApp weekly as a news source. A recent report from New York University’s Center for Business and Human Rights warned that WhatsApp “could become a troubling source of false content in the US, as it has been during elections in Brazil and India.” It’s imperative that news media figure out how to map the contours of these opaque, unruly spaces, and deliver fact-based news to those who congregate there. Journalists must experiment with different ways to identify and engage the chat-app influencers and networks that can amplify quality journalism.

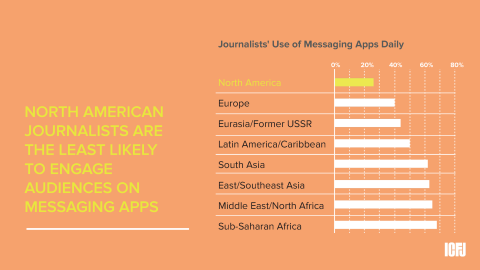

If journalists don’t step up, audiences won’t find much credible news on private messaging apps. Over the past two years, according to our survey, newsrooms in seven out of the eight global regions we examined have cut back on the use of these apps as a distribution platform for their content. The steepest drops occurred in Eurasia/ former USSR (20 percentage points), Europe (16 points), and North America (10 points).

It seems likely to us that the initial excitement of experimenting with yet another publishing platform soon dissipated, particularly as journalists realized the apps aren’t designed for wide distribution of content. Messaging apps are built for groups of a few hundred users—not large enough for a news publisher to easily distribute content (as German news outlet inFranken.de discovered), but more than enough to share links to conspiracy theories, or upload dubious videos and photos. And the platforms aren’t eager to support tools to enable publishing. In December, WhatsApp shut down the ability of publishers to send bulk newsletters.

Yet messaging apps remain great for engaging audiences—by responding to questions, or crowdsourcing, or receiving texts, photos, and videos during breaking news or making the editorial process more visible and accessible to readers, as is happening in countries including Brazil, Rwanda, and Israel.

Journalists in many parts of the world are doing that. Our 2019 survey showed a spike in their use of messaging apps to directly interact with, and respond to, readers and viewers. More than two-thirds (69 percent) engage their audiences at least weekly via instant messaging. Sadly, in the U.S., where chat-app usage is lower, it’s only 26 percent. Still, more than 100 million Americans use Facebook Messenger. U.S. journalists clearly need to engage—and experiment—more.

They should also be mindful of vulnerable communities. Immigrants to the U.S. tend to use chat apps more frequently to communicate with family back home, making them targets for disinformation. Chinese-Americans are already being flooded by Chinese government disinformation on Tencent’s WeChat app, and even more so in the wake of the Hong Kong protests. With foreign governments likely to step up their interference in the 2020 elections, journalists can serve as a reality check on the distortions likely to appear in these dark spaces.

Read more about ICFJ's 2019 “State of Technology in Global Newsrooms” survey.

Main image by Rodion Kutsaev on Unsplash.